Authored by Anna Kallschmidt

The opposition to increase wages to be “livable” is actually not always heartless. While it may be shocking that some disagree that paying people well enough to afford basic needs (such as healthcare), a major concern that many opposers have is that increasing wages will make employees so unaffordable that they will actually lose their jobs.

When employers have to pay their employees more, they are concerned they will lose profit. This perception has had a devastating impact on low-wage workers; for example, when Wendy’s increased their minimum wage, they also eliminated 31 hours of labor per location every week.

Fortunately, GLOW researcher Dr. Molefe Maleka discovered there is a benefit to employers for retaining employees who are paid a livable wage.

A living wage is composed of three facets: a living standard, the number of persons supported by the living wage, and the number of individuals in the household expected to work full-time to provide support. For this study, a living wage was defined as an income earned by workers that is high enough to meet their basic needs and enable them to live a good-quality life.

In order to assess these HR outcomes, a population of low- and middle-income workers in South Africa responded to a survey, which assessed their demographics, quality of life, quality of work life, working arrangements, pay, and living arrangements. With this data, the researchers were able to assess the relationship between household income, and the dependent variables of fairness, dignity, and quality of life.

Wait, why are we talking about fairness, dignity, and quality of life?

Because these actually are important organizational outcomes.

A common mistake employers make is to only use the consumer price index to determine wages. However, this method does not allow employers to understand how wages impact employees’ behaviors. When workers earn a living wage, they are more motivated and their morale is higher, which has been proven to increase their commitment to their employers as well as improve their job performance. These workers also have higher life satisfaction, and they make their employers profitable, sustainable, and efficient. Additionally, when workers do not perceive their pay as fair, and they are not unionized, they may initiate illegal strikes, which can make workplaces ungovernable and unprofitable.

Society also suffers from employees being kept in poverty. Having employees who cannot afford to save money impacts future welfare spending because the government will have to pay retired low-income workers a social grant, as they will not be able to afford it. Additionally, employees who earn wages below the poverty threshold cannot afford basic needs such as medical care, which creates an unhealthy society because people remain ill due to unaffordable treatments.

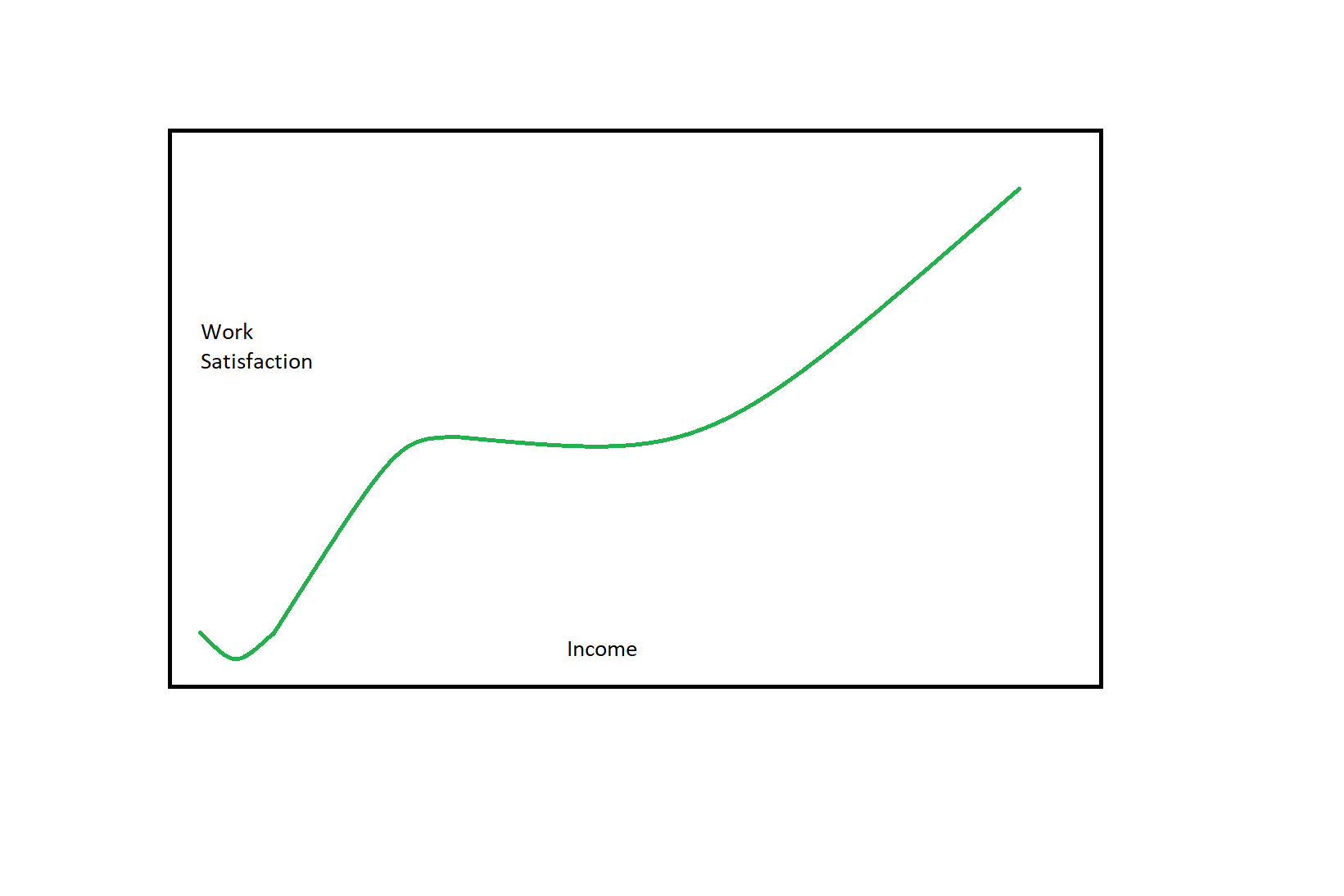

Dr. Maleka’s work did find that living wages do impact all of the predictors of these powerful outcomes. Interestingly, he found that the relationship between household income and fairness, quality of life, and dignity was S-shaped. Consistent with other GLOW research, a certain bracket of income has to be reached in order for employees to benefit from work and life outcomes, which has been coined the “poverty trap,” which is the phenomenon of a “flat-rise-pause-rise” curvilinear function where people in both New Zealand and South Africa did not experience quality of life or quality of work life below a household income of $40,000 NZ dollars per year.

While Carr and colleagues found that in order to reap the benefits of satisfied employees, wages must stay above the plateau of the poverty trap, Maleka’s work supports that in order to achieve important human resources outcomes, this poverty trap must also be avoided.