Authored by Anna Kallschmidt

Poverty is such a pervasive global issue that research by the PEW Research Center found that 71% of the globe lived on under $10 a day in 2011. With such a overwhelming percentage, it can be difficult to know where to even begin in fighting it. However, if you’re an organizational scientist, the United Nations and Project GLOW have a list of objectives for eradicating poverty around the world.

Project GLOW (Global Living Organisational Wage), is a global network of researchers initiated by Dr. Stuart Carr at Massey University in New Zealand. GLOW researchers aim to answer the question, is there a global living wage that permits people, communities, and organizations to thrive?

The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include the mission to annihilate poverty and inequality through inclusive industrialization and decent work. In 2018, GLOW generated specific research questions that organizational scientists around the world can investigate in order to fulfill this international mission.

“The 2018 paper is a sign that GLOW is gaining increasing traction and engagement with the SDGs. In fact the paper has a table of suggested applied policy research questions around each of the SDGs, which may be useful to glow hubs as they define their agendas.”- Stuart Carr, Ph.D.

In the 2018 paper, recently published in Sustainability Science, Dr. Carr and a host of international GLOW researchers took the lead on addressing these SDGs by investigating the question, is any wage a good wage? The results of their study imply that if you are an employer, paying your employees too little, might actually not be benefitting society or organizations.

The authors measured Fairness (regarding fair wages for the job, their effort, their qualifications, and comparison to other similar jobs), Quality of Work Life (assessing job satisfaction, empowerment at work, and occupational pride), and Quality of Life (quantifying life satisfaction, physical well-being, and mental stress).

It is important to note that NZ and South Africa differ socio-economically, socio-culturally, and socio-politically. NZ has a relatively egalitarian economy, but South Africa has consistently the highest level of income inequality. Even so, the findings replicated across contexts. Consequently, a common required living wage between the two locations indicates a substantial contribution to the organizational science regarding living wages, as similar results regardless of the drastically different surroundings indicate a robust conclusion.

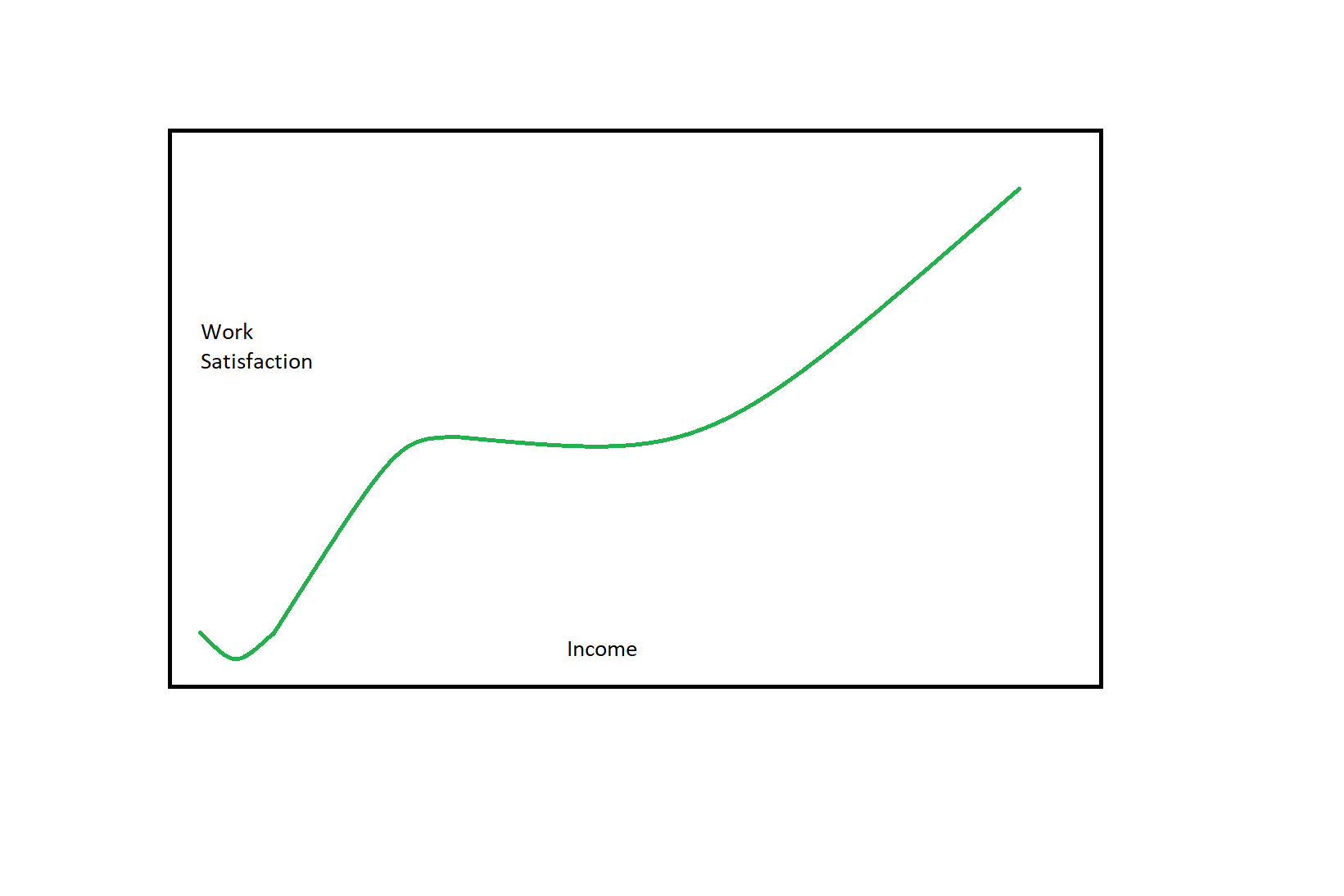

Both countries’ data also indicated evidence for a “poverty trap,” where there was reduced quality of work life and life for people living in this trap. The results indicated a “flat-rise-pause-rise” curvilinear function for quality of life and quality of work in New Zealand.

In New Zealand, the line was mostly flat for quality of work through the households with income at and below $40,000 NZ dollars. This indicates the “poverty trap,” which was even more prevalent in South Africa, where there is more severe hardship.

Interestingly, the same relationship was not found for life satisfaction in New Zealand , but there was a significant curvilinear relationship for South Africans. Again, the relationship had a “flat-rise-pause-rise” pattern, which suggests further evidence for a “poverty trap,” where there was less life satisfaction for people unable to pay for their basic needs.

Furthermore, examination of the measures discovered that perceived fairness predicted both work and life satisfaction; however, fairness accounted for a larger percent of the satisfaction in South Africa than in did for workers in New Zealand. Collectively, the evidence reveals that perceived fair wages do predict important work and life outcomes; with data from New Zealand and South Africa reporting that an income of at least $2,000 per month is necessary for employees to reap important work and life outcomes.

Furthermore, just above this living wage minimum, there is a dip in in organizational and life outcomes, which may indicate the importance of relativity. When someone is just outside of poverty, they are still on lower end of the upper-income distribution, which may result in these people still being aware of their deprived state compared to their peers, even though they are not technically in poverty.

Is something better than nothing when it comes to wages? In order to reap the benefits of satisfied employees, wages must stay ahead of the cusp of the curve of the poverty trap.

What future steps are needed for researchers? The 2018 paper has a table of research questions that still need to be answered in order to reach the UN’s SDGs.

“In New Zealand, we are using the table to help us refine our Marsden-Funded project, which is a multi-sector, multi-stakeholder, multi-method, three-year longitudinal study of how changes in wage levels relate to changes quality of life, and work life, across time. A key focus is placed on both employee and employer perspectives and experiences, in the wake of planned rises in the legal Minimum Wage. The project includes a strong emphasis on Maori and Pasifika groups, who are over-represented in this county in our low-wage employment statistics. The project includes a number of student theses, from honors and master’s to doctoral level, since in keeping with GLOW’s objectives and ethos we are seeking to build research capacity/capability. We are aiming all the way through to keep our eye on policy implications, and to that end have built in a dissemination plan that includes policy briefs to employer federations, labor unions, & government.” -Stuart Carr, Ph.D.