Authored by Anna Kallschmidt on behalf of Prof. Rosalind Searle, Drs. Ishbel McWha-Hermann, Mahima Saxena, Bimal Arora, Divya Jyoti, Christian Seubert, Lisa Hopfgarner, and Jürgen Glaser

As with most events in 2020, SIOP 2020 was a little different this year. The umbrella organization of industrial-organizational psychologists hosted its annual conference virtually this year, in order to support the spread of science without COVID-19. While our efforts to end poverty and world hunger at Project GLOW have always been imperative, the modern pandemic has shed painfully harsh light on these inequalities. Thus, Project GLOW’s panel session “Siop Select: Living Wage, Workplace Well-Being: Contributions From Project GLOW”, was even more relevant than ever.

The session was supported by the Alliance of Organizational Psychology, which is an alliance from associations around the world, which have a combined mission that fits well under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs), especially the first goal.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Labour Organization (ILO) stated that adddressing poor work conditions was the number one priority for the world of work. Established in 2016 and spanning across 26 countries, GLOW has been ahead of this call, working to answer the question, “Is there a Global Living Wage that enables people, organisations and communities to prosper and thrive?” Thus, the panel of GLOW scientists at SIOP 2020 displayed novel work for living wage workplace psychology, which could be foundational to the world of work recovering from this pandemic.

Prof. Stuart Carr, the founder of Project GLOW, stated that “COVID-19 has amplified the need to solve the puzzle, each of these scientists are working on important pieces of that puzzle.”

The four-part panel began with “Project Glow: Insights from a systemic review of living wages” by Dr. Ishbel McWha-Hermann at the University of Edinburgh and Prof. Rosalind Searle at the University of Glasglow. The research team conducted a review on research showing the impact of living wages.

This research is essential because employment is one of the most important ways to pull people out of poverty. The pandemic has further illuminated how unemployment and reduced work have exacerbated poverty. Even so, the researchers share that economists and neo-liberals have argued that interventions that increase wages distort the labor market and threaten employment. Yet, work psychologists have been dismantling this argument and showing it is not true through developing a person-centric view of low wages and looking at the impact that low wages vs. living wages can have on employee wellbeing.

The researchers share three main arguments from Adam Smith, a historic supporter of living wages.

- Sustainability: People need a living wage in order to continue to provide labor, as they must feed themselves and their families, obtain an education, and engage in society).

- Capability: Individuals are able to increase their productivity when they are capable of making choices that help them plan a future trajectory.

- Externalities: Science must understand the societal impacts of not paying people a living wage.

The authors examined 115 papers in this area. A key takeaway from this review is that past work was mostly centered on an employer-focused approach, attempting to identify a wage that has an impact on an employer and shareholder return. For psychologists, it is important for us to show a person-centered view, which unpacks employees’ quality of life at work and home, capabilities (freedom through choice), and decent work (job satisfaction, job security).

The authors identified substantial gaps in the literature that psychologists must make efforts to address.

- Single jobs: How does a living wage impact people? Does it give people the choice of having a single job? Does that mean there is more leisure and recovery time? Does this leisure and recovery time increase the employee’s viability?

- Capability and Identity: How are people spending their time when they have a living wage? Does more time mean people actively improve, or do they spend more time vicariously improving?

- What does a living wage change?: Does it influence self-efficacy, career goals, affective commitment to an employer, pride in the employer, societal engagement, or trust?

These panelists were followed by Dr. Mahima Saxena, whose work built beautifully off of this call for more living wage research. Dr. Saxena investigates socially responsible supply chains and their role in providing living wages, promoting decent work, and improving employee well-being, especially for workers in the informal economy. The informal economy is the facet of the workforce that is not protected by the state, representing over 2/3 of the world’s workforce. Informal workers can be highly skilled, but they are often severely disadvantaged (i.e., increased safety risks and economic tenuousness, lack of living wages, etc.). Dr. Saxena states that living wages for informal workers are essential, as they act as an enabler for perceptions of justice, equity, life satisfaction, and boosting quality of life and human thriving beyond mere existence.

Living wages have been argued to be a fundamental facet of decent work, which is the eighth UNSDG. Thus, Dr. Saxena’s work proposes prioritizing socially responsible supply chains. She states that a main inhibitor to a whole and complete life, especially for highly skilled workers in the informal economy, is economic tenuousness, such as low wages and financial uncertainty. These workers struggle with the inability to have consistent sales and their products are often underpriced, or available on inadequate sales platforms, where the profits are swallowed by the presence of middlemen along the supply chain. These middlemen profit off of the exploitation of the informal worker, who is also the creator of the product.

Dr. Saxena proposes having supply chains that directly link the artisan to the customers, which can promote fair prices and a decent income, and remove unethical middle-man practices and the uncertainty and precariousness associated with sales and pricing. Taking away the precarious nature of income can reduce economic tenuousness, encourage living wages, and enhance well-being. Furthermore, she advocates that supporting informal workers with living wages and socially responsible supply chains can play a critical role in preservation of cultural skills that may otherwise rapidly erode.

Dr. Saxena was followed by Drs. Bimal Arora and Divya Jyoti, who call for a methodological reflection on the living wage research in the context of supply chains for both formal and formal workers. The researchers revealed that recent studies have highlighted that the commitments to pay living wages in their global supply chains have not been fulfilled. The research team states that these shortcomings are due to:

- Confusion about living wage definition

- A lack of transparency of wage data

- No clear roadmap on how to proceed with living wages

- Corporations outsourcing commitments to multi-stakeholder initiatives

- Reliance on flawed social auditing

- Freedom of association not realized

Drs. Arora and Jyoti explain that while researchers have identified the barriers, there is little understanding about why these impediments exist and persist. They state that one reason for the limited knowledge of living wages is due to an over-reliance on quantitative research approaches.

Reflexive and qualitative research has been upheld for illuminating unrecognized possibilities, but use of this method has been limited. -Drs. Arora and Jyoti

Consequently, the research team requests ethnographic studies on supply chains. Ethnographic methods allow researchers to take a deep dive into understanding people’s actions and experiences of their world and use it to explicate ways in which people come to understand, account for, take action, and manage their day-to-day situations. Thus, there is a methodological fit between ethnographic research and living wage research in supply chains, since research on supply chains and living wages is in a relatively nascent stage.

The researchers propose three levels of ethnographic studies on living wages and supply chains:

- Institutional Level: Focus on the living wage discourse (i.e., motivations, interests, negotiations, politics)

- Organizational Level: Focus on the organizational processes, practices, work performance, wage management systems, etc.

- Individual level: Focus on individual experiences and lives in and around work and wage; employees’ wage satisfaction, personal life, familial relationships, assumptions; and challenges of managers and other stakeholders.

For example, the authors recall an organization who paid living wages to their workers in factories in South India. However, when the money was dispersed, it was labeled as a bonus instead of an increased wage provided by the company. The authors propose that an ethnographic study could examine the rationale and process of an implementation and possibly explain why this approach was adopted. It could also highlight the individual experiences of living wages, such as the impact on employees’ lives and familial relationships.

In an ethnographic study conducted by Dr. Jyoti, it emerged that women workers in the factory prioritized their flexible work schedules over monetary compensation. Therefore, Drs. Arora and Jyoti explain that ethnographic studies are important because they can illuminate which components of the living wage can be influential beyond only the economic components of a living wage. Furthermore, ethnographic research can illuminate the dilemmas that leaders and organizations experience when they try to balance living wages with profits. Collectively, the authors state that the meaning of an organizational wage is important to recognize beyond an economic value.

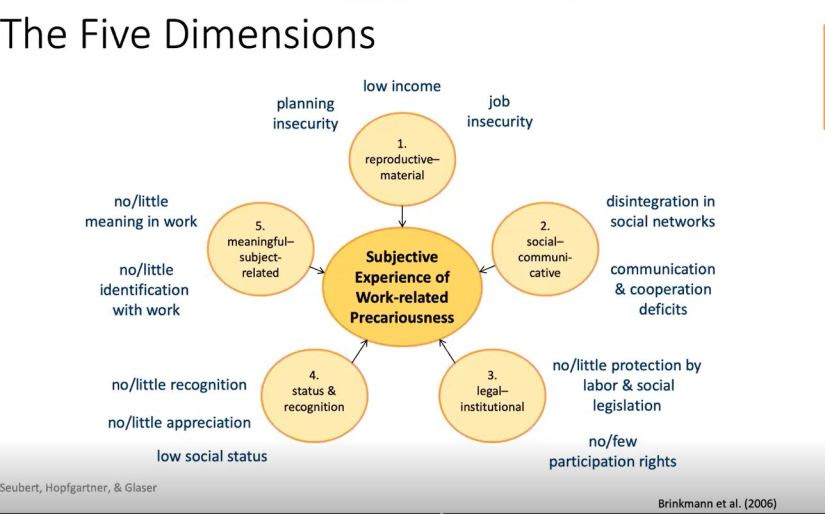

The session was appropriately concluded by Drs. Christian Seubert, Lisa Hopfgarner, and Jürgen Glaser. Their research explores living wages beyond solely economic metrics, by examining the subjective experiences of precarious employment.

“Standard (i.e., “normal”) employment is characterized by permanent full-time employment with secure income, full integration into social systems, identity of work and employment relationships, and employees bound by instructions. On the contrary, atypical employment exhibits flexible working hours and locations, a reduction in full-time employment, and an increase in part-time work, fixed-term work, labor leasing, and dependent self-employment.”- GLOW blog, Feb 2020

Precarious employment opens a broader perspective past “job insecurity” to decent employment conditions that enable quality of work and life. The living wage concept is extended from subsistence-oriented minimum wages to meaningful participation at the workplace and society. Attributes of a job with precarious employment include employment insecurity, income inadequacy, and a lack of rights and protection. The authors are in the process of validating an instrument to measure the subjective experience of work-related precariousness, which currently consists of five dimensions.

The researchers gathered data from 1196 individuals. To date, hierarchical regressions show these dimensions can predict emotional exhaustion, depression, and work engagement. This scale also predicted additional variance in these criteria than solely measurements of income. Furthermore, the scale was the strongest or second strongest predictor for each criteria.

The authors hope that this scale can be used in combination with objective measures to research work precariousness, particularly to contribute to research on living wages and decent work.

“We suggest an inversion of the 5 dimensions of precarious employment, with living wages as a core element, in order to identify key drivers for the development of human capabilities through decent employment conditions.”- Dr. Christian Seubert

Clearly, the four research teams here have produced groundbreaking work on living wages; however, they revealed many critical avenues for future research. Interested researchers are invited to join Project Glow, regardless of academic tenure — students, early career, teachers, and practitioners are all welcome. Prof Carr encouraged those who are interested in joining the team to register at https://projectglow.net via the contact us page.